Entropy and Empire

Posted by Stoneleigh on March 20, 2007 - 11:45am in The Oil Drum: Canada

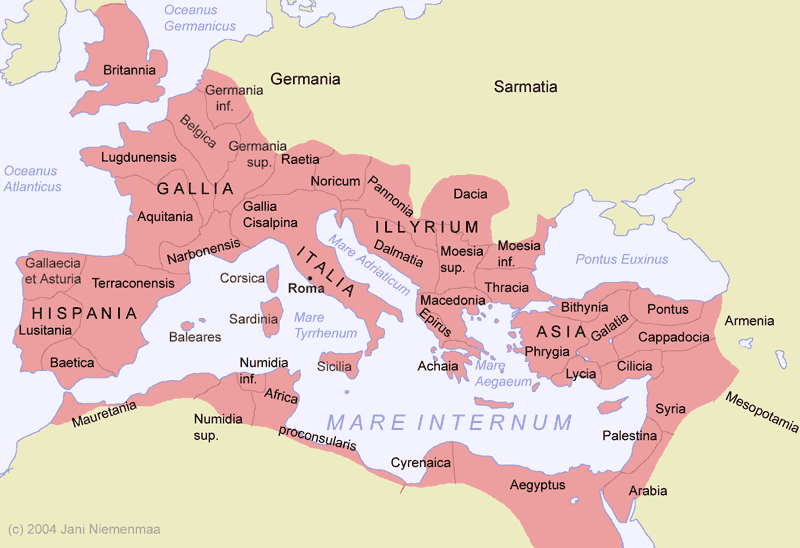

In his recent book The Upside of Down, a review of which can be found here, Thomas Homer-Dixon interpreted the development of the Roman Empire in terms of thermodynamics. The success of the empire depended on its ability to extract energy surpluses, in the form of food, from the imperial territories and concentrate them at the centre, where they enabled the development of a tremendous degree of organizational complexity. Without a large, and growing, hinterland to collect surpluses from, complexity on such as scale would not have been possible to establish and maintain.

But wherever the farms were located, they played a role in the Roman energy economy similar to that of solar battery chargers: they converted sunlight into a form of high-quality potential energy, especially fodder and grain, that was storable and transportable.The Romans then focused this energy – they used their food batteries, so to speak – to create a productive, resilient, and phenomenally complex system of public buildings, manufacturing facilities, housing, roads, aqueducts, and social organization.

Thermodynamics and the Implications of Entropy

In thermodynamic terms, a highly uneven distribution of energy is an ordered state, and therefore a low entropy condition. Without a continual input of energy from outside the system, entropy within the system would increase, meaning that the relative concentrations would tend to equalize over time. Moreover, if the concentration eventually equalized, it would do so at a very low level. For instance, an even distribution of energy across the universe, which would theoretically occur eventually if the universe were to expand forever, would be called heat death – ironic, as it would be scarcely above absolute zero.

In order to generate a low entropy (ordered) state from a higher entropy (less ordered) state, energy external to the system is needed to drive the concentration of energy within the system uphill. However, entropy in the larger system must increase, in accordance with the laws of thermodynamics. If energy is to be concentrated at the centre, it must come at the price of a lower energy level in the periphery, and the energy loss in the periphery must be greater than the gain at the centre.

Click to Enlarge

A discussion of the thermodynamics of empire is not complete without discussing the implications of entropy. Many have argued that if only there were fewer people, so that we were living within the natural carrying capacity of the Earth, then all would be able to live at a modern standard of living. However, a modern standard of living requires a very high concentration of wealth – wealth being a proxy for energy, as wealth represents a valid claim on available energy and resources. For enough relative wealth to accumulate in a political centre for a complex civilization to develop, there must be a much larger periphery available to be relatively impoverished in providing the necessary energy subsidy. An equal distribution would, in accordance thermodynamics, only be possible at a low level for all.

The Centre and the Periphery - Then and Now

With solar energy as their external energy source, Rome was able to subjugate a larger and larger expanse of the surrounding territory. It derived a progressively greater total energy subsidy with each conquest, at least until it reached the point where the energy necessary to perform distant conquests became too large in relation to the energy subsidy Rome could hope to gain for itself in the process – a net energy limit. Essentially, Rome managed to establish a long-lasting ‘wealth conveyor’ in its favour, through the imposition of imperial social, economic and legal structures on the territories of the periphery.

Beginning in the third century BCE, Roman expansion transformed the capital of other societies into resources for Rome as country after country was conquered and stripped of movable wealth. (from How Civilizations Fall: A Theory of Catabolic Collapse, by John Michael Greer)

Codified laws regulated everything from money and debt to property rights, corporate organization, guilds and the empolyment of labour and slaves. (from The Upside of Down, by Thomas Homer-Dixon)

There are obvious parallels between the Roman situation and our own, both from the point of view of political centres and from the perspective of the hinterland. The solar energy subsidy available to the Romans allowed them to create a concentration of ordered socioeconomic complexity in a sea of relative disorder and and simplicity, driving entropy in reverse locally. Western industrial economies, and more recently other competing centres of political power in the era of globalization, have been able to do the same, but to a much greater extent due to the very much larger energy subsidy provided by fossil fuels. The centres have seen spectacular gains in complexity, while the hinterland has stagnated, to a greater and greater extent over time.

Indeed, in any complex society, those of us who aren’t farmers are essentially parasites on those of us who grow the sources of energy – the grain, vegetables, fruit and meat – that keep all our bodies running. (from The Upside of Down, by Thomas Homer-Dixon)

Although there is currently no center which claims direct political control over a large periphery as Rome did (a de jure empire), there is nevertheless at least one de facto empire in the form of the industrialized West, and more specifically the United States. The economic power of the US (with its reserve currency advantage) to determine the terms of international finance and trade, backed by its military strength and extensive network of permanent military bases, has resulted in the ability to entice, cajole or coerce a large periphery into accepting life on the terms of the ‘imperial’ center. This has involved the monetization of peripheral economies, often in tandem with leading those nations into a deep indebtedness thereafter managed through structural adjustment programs by quasi-imperial institutions such as the IMF. The net effect has been the debt enslavement of whole nations, despite their putative sovereignty, as the established wealth conveyor carries resources and surpluses to the center while leaving most of the externalities behind.

We are entering a bifurcated world. Part of the world is inhabited by Hegel’s and Fukuyama’s Last Man, healthy, well fed and pampered by technology. The other, larger, part is inhabited by Hobbes’ First Man, condemned to a life that is “poor, nasty, brutish and short”. (from The Coming Anarchy, by Robert Kaplan)

A political centre gains the ability to create order - a highly differentiated society capable of monumental architecture - at the cost to the periphery of a greater loss of order. The centre gains resources while avoiding many unpleasant externalities, but the periphery must suffer a loss of both resources and surpluses due to labour, and must tolerate all the externalities involved in providing for itself and for the centre. Many parts of third world periphery - stripped of resources and burdened with externalities - now verge on anarchy, as there is too small a concentration of energy left locally to support an ordered state.

Sierra Leone is a microcosm of what is ocurring, albeit in a more tempered and gradual manner, throughout West Africa and much of the underdeveloped world: the withering away of central governments, the rise of tribal and regional domains, the unchecked spread of disease and the growing pervasiveness of war. (from The Coming Anarchy, by Robert Kaplan)

Entropy and the Twilight of Empire

Rome eventually hit a net energy limit and could no longer sustain its internal complexity. Efforts to strengthen the wealth conveyor through repression during the reign of Diocletian - an elaborate, highly intrusive and draconian regime of taxation in kind - amounted to feeding the center by consuming the productive farmland and peasantry of the empire itself. This period represented a brief reprieve for a political center declining in resilience, at the cost of catabolic collapse. Regions incorporated into the empire declined to a lower level of complexity than they had attained before being conquered.

Thus Britain in the late pre-Roman Iron Age, for example, had achieved a stable and flourishing agricultural society with nascent urban centers and international trade connections, while the same area remained depopulated, impoverished, and politically chaotic for centuries following the collapse of imperial authority. (from How Civilizations Fall: A Theory of Catabolic Collapse, by John Michael Greer)

No longer able to project power at a distance, or to defend the concentration of wealth (and therefore energy) which had permitted entropy to be held at bay, the western Roman empire fell. The result was the loss of an ordered state - with sharp disparities in energy concentration and resultant socioeconomic complexity - in favour of a more even distribution of both. When entropy finally gained the upper hand, concentrations of wealth, and the claim to energy represented by wealth, were impossible to sustain. Equalization at a low level was the natural outcome in the area of the former empire, although wealth conveyors in favour of other centers, such as the eastern empire, strengthened in their turn. Rome itself remained a backwater for a thousand years.

The ability to concentrate wealth from the surrounding area arguably proceeds in cycles of ascendancy, supremacy and decline. A new center begins to develop, often by being the beneficiary of wealth diversion from an established center where the citizens would rather buy the labour of others with their accumulated wealth than engage in labour themselves. Services persist in a decadent centre, but real wealth creation is out-sourced, perhaps allowing a new center to reach critical mass - at which point its development would become self-sustaining. For instance, the gold of Spain at the height of its power established industry in Britain, the Netherlands and elsewhere in Europe.

As one Spaniard wrote at the time:

Let London manufacture those fabrics of hers to her heart’s content; Holland her chambrays; Florence her cloth; the Indies their beaver and vicuna; Milan her brocades; Italy and Flanders their linens, so long as our capital can enjoy them. The only thing that it proves is that all nations train journeymen for Madrid and that Madrid is the queen of Parliaments, for all the world serves her and she serves nobody. (quoted in The Wealth and Poverty of Nations, by David Landes)

New centres grew in power, while a decadent Spain declined into inward-looking repression as the supply of gold ran out. According to David Landes:

By the time the great bullion inflow had ended in the mid-seventeenth century, the Spanish crown was deep in debt, with bankruptcies in 1557, 1575 and 1597. The country entered upon a long decline. Reading this story, one might draw a moral: Easy money is bad for you. It represents short-run gain that will be paid for in immediate distortions and later regrets. (from The Wealth and Poverty of Nations)With the transfer of wealth, and eventually the power to concentrate wealth from the surrounding area, also comes the transfer of hegemonic power. Britain in turn exported wealth to North America, and in doing so spawned a competitor with the luck to have access to a hitherto unexploited continent. The American Century has been the result.

In recent years, the wealth conveyor in favour of the industrialized West has appeared to be approaching natural limits. In freeing capital to seek a lower cost base through globalization, the West has fed the development of major new competitors in Asia. In addition, the supply of fossil fuels, which have served as the external energy source driving the accumulation of wealth, is arguably approaching a net energy limit. Social order in parts of the periphery is becoming so compromised that further resource extraction may no longer be possible.

West Africa is reverting to the Africa of the Victorian atlas. It consists now of a series of coastal trading posts, such as Freetown and Conakry, and an interior that, owing to violence, volatility and disease, is again becoming, as Graham Green observed, “blank” and “unexplored”. (from The Coming Anarchy, by Robert Kaplan)

If the West follows in the footsteps of Rome before it, one would expect that the loss of the ability to access new energy subsidies, or even maintain current energy flows, would result in the development of the same repressive, catabolic process that temporarily reinvigorated Rome under Diocletian. The implications for surrounding territories could be unpleasant.

Eventually, the ability for the old centre to project power at a distance, or perhaps even to hold together as a nation would be lost, as the mechanism for concentrating wealth at the center would break down. After that, entropy would be expected to run its course, resulting in the relative equalization of wealth, and therefore energy, between the old center and its erstwhile periphery.

The Rise of a New Centre?

The interesting question for the future would be whether the developing competitors - initially fed by exported Western capital but now reaching critical mass as new centres in their own right - would be able to achieve self-sustaining development as capital exports from the old centre cease. If so, the primary wealth conveyor would be re-established in favour of a new centre and, as has happened many times throughout history, hegemonic power would eventually follow.

However, the developing Asian centres are as dependent on energy subsidies in the form of fossil fuels as the current Western centre, and also as vulnerable to the effects of climate change, water scarcity, pollution and financial instability. It is difficult to imagine a smooth transition of political and economic power to a new centre while carrying capacity is arguably shrinking in all regions even as population continues to expand. If a new cycle of ascendancy is to begin elsewhere in due course - catagenesis, to use Homer-Dixon's phrase - it appears unlikely to do so without a considerable increase in entropy in the meantime.

Sadly, though, history shows that most human civilizations over-extend the growth phase of their adaptive cycle, so they eventually suffer deep collapse. "A long view of human history reveals not regular change but spasmodic, catastrophic disruptions followed by long periods of reinvention and development," writes Holling. (from The Upside of Down, by Thomas Homer-Dixon)

Digg, reddit, linkfarms. :)!

I read this book a month or so ago and thought it was excellent, although not as solution filled as the title would suggest.

This article is an attempt to extend part of the thesis of the book.

Good job, Stoneleigh. Bringing Spain into the picture is particularly instructive.

Excellent thread everyone!

It's so pleasant to see an intelligent discussion without the sniping and nastiness that even TOD can exhibit nowadays.

The links seem to have a bit of a problem, being prefixed with http://theoildrum.com,

Peter.

The problem is Stoneleigh is using funky quotation marks. HTML doesn't recognize them.

I will try to fix them.

Yup, it was the quotation marks. Using ” instead of "

Thanks Leanan. It comes from composing in Word, but I had no idea it made any difference. I'm glad there are people here who know more about these things than I do.

A brilliant analysis IMO. The author recognizes that food is stored solar energy and lays out the thesis that energy vulnerability contributed to Rome's fall. It's easy to see the foreign parallel with the USA. Less obvious to some is the internal parallel in the USA. California is the de facto center of culture and science, the source of much innovation and progress. It is also an energy island, partly of its own making, just at the central government has isolated itself from the larger world with its energy policies. IMO much of the anti ethanol rhetoric found here comes from California and its realization that it may be so vulnerable as to lose power to the hinterlands. The Midwest is held in contempt just as Rome viewed the barbarians as uncultured and backwards. From its de facto control of science it develops arcane and irrelevant theories like EROEI to maintain its position of power. But the barbarians know the center energy island is vulnerable and keep up the pressure. Over time the power shifts. The bright side for California is that there is still a Rome and there will always be a California, just not as arrogant and powerful.

irrelevant theories like EROEI

Right. 1 unit consumed to produce 100 units (99 net) in the early days of oil. 1 unit consumed to produce (maybe) 1.3 units (0.3 net) for corn ethanol. No relevance whatsoever. Sheesh!

Ethanol: work harder, not smarter.

EROEI is irrelevant as long as its positive - which it is.

The Petroleum Input Ratio or PIR is all that matters there after.

...and we have an infinite amount of land to grow things.

There is a perspective on eroei that renders the fossil-fuel-proportion argument irrelevant in objective discussion. Instead of considering individual fuels, consider the _average_ eroei of fuels available to civilization. This average eroei is currently about 10. (Robert Kaufman), about the same as the current eroei of fossil fuels.

The implications of a much lower average eroei are clear and stark. The eroei is the ratio of the energy obtained to the energy that must be dissipated to obtain it. If the average eroei of all energy sources is 10, then out of every 10 units of energy we produce, we get to keep 9 units of energy for uses other than energy production (or 0.9 out of 1). If the average eroei of all energy sources is 3, then out of every 3 units of energy we produce, we get to keep 2 units of energy for uses other than energy production (or or 0.67 out of 1).

Consider what this means for total energy production. The society with an eroei of 10 produces 1.1 units of energy for each 1 unit of energy needed for purposes other than producing energy. The society with an eroei of 3 produces 1.5 units of energy for each 1 unit of total energy needed for purposes other than producing energy, 1.5/1.1 = 1.36, 36% more total energy production per unit of energy needed for purposes other than producing energy than the society with an eroei of 10.

Maybe I'm just a total idiot, but this appears to be a rationalization that eroei of newer fuels is irrelevant because the rest of society's non-energy producing eroei will make up for whatever the eroei is for newer non-fossil fuels.

That may be true if the energy producing eroei remains positive. But what makes you think that civilization is going to increase its non-energy producing eroei ENOUGH to make up for a declining energy producing eroei? Nice comfy theory, but where is the data?

And once net energy producing eroei becomes negative, is that still okay as long as society can make up for it in other areas? It all nets out? This sounds like gobble-de-goop rationalization to me. I hope you feel better, but I don't.

You can eternally run faster to stay in place, but that sounds pretty tiring to me.

Hi. As a new TOD member, I can't seem to find a

way to message posters, but I'd be interested in

being in touch with the several who hie from the

big isle, where I'm planning to move for PPO-

related reasons.

Great discussion in this string, BTW.

email me if you like, at dj@hawaii.rr.com

best

An easier way to say this is:

It's all about energy flow

If the net energy flow into civilization decreases (due to a declining average eroei), and this is not compensated by efficiency gains in energy consuming activities, civilization will decline.

JoulesBurn

I think that depends upon how you define civilization, almost the opposite statement seems to be the case.

Gandhi on Western Civilization, "I think it would be a good idea"

EROEI of less than 1 works for me. All energy is not equal. Some are dispatchable others are not. Some are easily transported others are not. I'll trade 100 units of "lousy" energy for 99 units of "quality" energy and do very well.

We can choose energy units or petroleum units or economic units ($) to compare input and output. If we use economic units (and we have a free market) we will see the best use of resources. Markets aren't free but they are still smarter than the politicians that everyone seems willing to turn their lives over to.

Welcome to the real world where you will never get anywhere close to that deal. Anyway, EROEI is more the issue with the initial production (or harvesting) of the 100 units of "lousy" energy. If that gets less than one, then it matters not how much money you throw at it.

Are you saying that an EROEI of 0.99 is too good of a deal in the real world? I use "lousy" and "quality" as relative terms. Energy production at any step of the process can make sense if the EROEI is less than one. Fuel should be characterized on several dimensions (BTUs, weight, volume, stability/volatility, transportability, etc.). To say that the relative values of fuel can only be represented by BTUs ignores other elements of value. The monetary value of fuels is the market's attempt to balance all of these characteristics.

Oh, please. One of the biggest debunkers of ethanol is from Cornell, hardly in California. There are no energy islands in America. California, unlike some other parts of the country, recognizes that the globe, not just California, is in trouble, and is taking steps to pursue alternative energy sources. Any ethanol rhetoric found here comes from places like Montana (Rapier) and elsewhere. This has nothing to do with California. Your analysis reflects some sort of weird, reflexive hate of California that has nothing to do with reality.

As far as stored solar energy in the form of food, most of the country is heavily dependent on California, not the reverse.

Thank you.

There are no energy islands in America

Hawai'i. :)

Seriously, though, it's not yet, but it could be: You've got a relatively low population density, a 12-month growing season, a climate suitable for sugarcane, and really, really good soil in some areas. And recently, a political climate that is taking alternative energy seriously.

"Relatively low" is many times the number that it supported in the days of the ancient Hawaiians. And they were up against Malthusian limits.

Also, I suspect that it's unwise to pin all your hopes on a small island chain who's largest landmass is an active volcano...

-best,

Wolf

Yep, but that fits in with those that don't want to die slowly. Kaboom and it's over in short order.

The volcano is not really a problem, except that land overrun by lava takes a long time to become fertile again. So it could be bad news for farmers. And it can be heck on infrastructure, but they've sort of adapted to that. Lava used to destroy miles of roads, because it would hit the highway and then just follow it down to the sea. Now they design the roads on the Big Island with periodic dips, so the lava will flow across the road rather than along it, and destroy only small segments. (They do the same thing elsewhere in the world, in areas prone to flooding.)

Hawaiian volcanos have fairly low-pressure, liquid magma. They don't explode like Mt. St. Helens. I remember one time when the lava was crossing a highway. Everyone ran to go see. My uncle brought a trowel and was scooping up the hot lava and dropping coins in it, making souvenirs. Everyone was begging to borrow it.

You'd never do that at Mt. St. Helens.

The point that you are making is good, and the contrast with Mt. St. Helens is meaningful, but volcanoes are very unpredictable beasts. Explosive eruptions have occurred on Hawai'i. Large blasts simply don't appear to be the most common outburst from volcanoes built up from less-viscous (and therefore less-steam-trapping) sources of magma.

Take a look at: Explosive Eruptions at Kilauea Volcano, Hawai'i?

-best,

Wolf

Now darnit Leanan, I'm trying to scare everyone away.

Don't worry, once the aggressive homosexual pirates seize the Kona side and go to battle with the aggressive lezbian pirates who will have seized the Hilo side, people will stay away.

You forgot, "not that there's anything wrong with that," and change the z to s.

That's a relief.

A good friend whose wife works for the University of Hilo, and who contributed to the excellent tome, "Atlas of Hawaii," relayed the information that their geologists expect the next eruptions to be violent, similar to Mt. St. Helens, only they expect it to be the volcanoes on the WEST side of the island, not Kilauea. He said they expect the whole side of the island from North of Kona to Hawaiian Ocean View Estates at the south end to be blown to kingdom come. Now of course, if this happens, the immense VOG cloud and toxic fume clouds will likely kill everything on the island, so being on the east side won't help much. But for a few seconds, it might be the most incredible experience of a lifetime to see mother nature at work. Ultimately, she RULES and we are but her pawns.

So I recommend that everyone stay away, and 2/3 those that are here need to consider leaving.

I've been trying to feed one politician per day to Pele. When we had the big earthquake last fall, I really thought Pele was angry that we hadn't fed her nearly enough corrupt politicians as they just kept oozing out of the woodwork. It's so hard to get them to cooperate as you drag them to the point of offering.

Politicians and weathermen = Volcano food!

I remember St Helens...we live south and the ash was plenty thick enough but not like the downwind folks - egads. I have a jar of ash and it still smells of sulfur - 17 years later.

Depending on the winds, there are days when we get some pretty hefty whiffs. It is quite unpleasant and I usually leave. That will get more difficult as peak oil ensues.

Malthus was wrong--he made everything up. Seriously.

See the real story: http://www.monthlyreview.org/1298jbf.htm

Might make the argument for Texas also. Its got its own grid, it still produces oil and NG(plus has refineries for both), and has coal. The beginnings of a Wind industry are coming into place, and out west are large swaths of desert lands ripe for solar farms. I'd have to double check but I believe there are also some potential uranium mines out in the coastal plains that operated in the 1950s, but closed down later due to lack of demand and the political climate surrounding it.

Growing seasons are pretty long and due to the simple fact its large, can grow a variety of crops ranging from food stuffs such as wheat, corn, rice, and many types of fruits and vegatables as well as industrial crops such as cotton.

Population Density is about 90 people per square mile though certainly some areas are more weighted while others have less than 1 person per square mile.

Granted Texas is plugged into the rest of the American infrastructure, but if I had to place a bet on which continental state could go it alone with minimum impact, I'd put my money on Texas in a heart beat.

Texas is HORRIBLY HOT in the summer. Like being in a toaster oven. Texas also has the problem of the depletion of the Aquifer and not much in the way of other water sources. There is even talk of the return of the Dust Bowl.(and I'm not talking football) Do you realize how much of texas is just plain desert?

A toaster oven is being nice... Along the gulf coast its more like a steamer. A dry heat would be so much more preferable. But we also have the energy infrastructure to handle that AC load in the summer. The reverse logic also works, btw... in the winter we require very little energy for heating and frankly I'd be more worried about freezing to death than being heated to death.

That said, West Texas does indeed have water supply issues, but then almost nobody lives out there. East Texas is hill country with lakes, rivers, decent rainfall, and forests. Its not like the whole state is a desert.

All that said, I didn't say Texas was problem free, just that from an energy and food standpoint we are in pretty good shape(compared to many of the neighboring states).

My position remains unchanged, I'd put my money on Texas in a heart beat.

Do you realize how much solar and wind potential that could be?

Shhhh! Do you want them to come here?

Do you realize that should we get to the point where "you're putting you're money" on indiviidaul localities that means globalization will have broken down?

And with that will go the 5,000 mile supply chains necessary for your solar and wind machines?

No, I didn't think so.

True. That was driven home for me when we drove past the wind farm at South Point, in Hawaii, a couple of years ago.

It's only 20 years old, but most of the turbines are no longer working. They're missing blades, or just aren't spinning. They're just rusting hulks.

And Hawaii doesn't have any natural sources of steel or aluminum to build replacements.

Texas does have oil (still), and that will probably help. And I think being connected to the rest of the world is, overall, a good thing. The immigration may well be going the other way across the border.

It's weather that's the biggest concern for Texas, IMO. Not just the heat, but the changes that global warming will bring. Drier, in areas that are already pretty dry. And hurricanes.

That's very true and the climate here is extremely harsh on anything made of metal. It's almost astounding how quickly metal becomes part of the earth again...

Leanan,

I remember when you posted this photo (or one similar to it) about a year or so ago. It certainly made an impression on me, as the wind debate here in Vermont is a lively one, and all we usually see are photos of brand-spanking new turbines, not derelict ones.

How did these turbines, which must have been the subject of much fanfare when they were built, end up in such a terrible state? Was there simply not enough electricity resulting, not enough infrastructure to get the power where it mattered, a financial collapse of the owners? Or... what? Surely replacement parts could be shipped in?

The wind turbines migrated across the island on their own.

=)

All joking aside, Leanan you must expand. I'm curious too.

I'm not sure what happened. From the timing, I suspect the project was born out of the oil crises of the '70s. When oil got cheap, there was probably not much interest in maintaining the turbines.

Last I heard, they were going to raze them all, and replace them with newer, more efficient ones. (Probably inspired by the recent spike in oil prices.) But they were only going to do it if they could get tax credits, and that wasn't guaranteed. It wouldn't be profitable without the tax credits.

Hawaii is very environmentally-minded, and they're always willing to try renewable energy. But it never really seems to work out. The wind farms are only profitable if they are subsidized. The ocean thermal plant has been shut down. The geothermal plant was supposed to be one of many, but has been so expensive and caused so many problems that they are no longer planning to build any more.

When I was growing up, we had a solar water heater. But when my parents built their dream home in a better neighborhood, they didn't bother with solar. Without the tax credits, it wasn't worth it. And the solar heater was kind of a pain, too.

I guess this is why I have so many doubts about alternate energy. Even in Hawaii, which is in many ways ideal for renewables, they don't compare to oil. Which, in Hawaii, has to be shipped in. The economy depends on tourism, and there's lot of concern about oil spills...yet nothing compares to oil. Lots of sun, lots of wind, geothermal coming out the wazoo, no need for heating or air conditioning, really, and yet...they still can't get off the fossil fuels.

Maybe if oil gets really, really expensive, that will change. Or maybe the costs of the alternates will also increase, as the cost for raw materials, transportation, etc., increase with the price of oil, and we'll be chasing that receding horizon.

The problem is the tax on carbon, or the lack of same.

Wind is competitive if there is a carbon tax. The same is true of nuclear. It's not so much that coal is cheap, it's that coal doesn't pay the freight for the damage it does.

On solar water heaters, they work fine in many climates *if* you have a backup, for the cloudy periods.

For example in Greece I would say 90% have solar water heaters. And it's plenty cold in Greece in winter.

Great series of posts, Leanan, full of excellent points.

Thank you.

My brother worked on some of the early windmills in California in the 1980s.

There were a couple of problems plaguing the industry at that time. (1) Designs that were for lack of better term pure crap. Expensive to build, inefficient, undependable, expensive to repair and with significant parts availability issues. (2.) Operators that did not have either financial stability or the desire to make an economic return. Many wind farms were sold as tax shelters by people whose interests were almost exclusively in selling tax shelters and leaving no finger prints while doing so.

Why are the pictured machines sitting there rusting. Hard to say in this particular case but the problems generically are not hard to foresee if you wanted to pick up distressed wind farms on the cheap. Legal hassles up the wazzou with liens and ownership issues, uncertain state of repair, and at the end of the day machines that are probably inefficient, undependable, expensive to repair and with significant parts availability issues.

Wind power can work, but it has to be done right.

Worth remembering that that is also true of coal power stations, or diesel ones.

ie every technology brings with it a requirement for social and economic infrastructure.

Lots of oil fired capacity brought into Africa in the 60s and 70s sits rusting. Yet solar cells sell very well in places like Kenya: the grid power supply is expensive and unreliable, and a good solar collector can last 40 years.

you hit upon the kicker here leanon.

many of the mass scale wind and solar projects pitched here, would take 20 years to build. meaning at the late stage of construction one would have to go back and replace the turbines/pannels one put in at the start instead of finishing.

We are looking at the new Easter Island mystery. How did those towers get there, mommy?

Leanan,

Where did you find that great photo! Man, that's embarrassing, on the cover of those books about peak oil, the icon of the great crash, the end, is almost always a broken down rusting gas pump or well...and you up and find a classic picture of what was supposed to be the future....but already broken down rusty hulks....it could be an advertisement for the oil or nuclear energy...."Here is your future, and it's already in ruins! "Why you can't make it without us."

Seriously though, one wonders whether the windmills you show really suffered from a lack of steel or aluminium to build replacements, or more likely, a 25 year run of givaway cheap fossil fuels simply caused the investors to lose interest and walk away from them, creating the real shortages: WILL and INVESTMENT.

Leanan, I am so very seriously worried that this is what we may be facing now. If the "peak NOW, and we KNOW we are right this time!!" crowd are wrong, even by only a decade or so, and fossil fuel prices fall through the floor, we could see every serious effort at alternatives end up just like this.....rusting junk. It won't be from lack of materials, or lack of technology. It will be from lack of WILL and lack of INTEREST AND INVESTMENT.

And it will be too late when the real thing comes to create and implement a mitigation plan then, and get the rusty junk up and running...we won't get another chance like we have right now.

This IS the pivotal time.

Roger Conner Jr.

Remember, We are only one cubic mile from freedom

I took that photo. It's a little bit blurry because I took it from a moving vehicle. (A politically incorrect Ford Explorer. Though there were five people in it, and many roads on the Big Island do require off-road type vehicles. Before SUVs became so popular, almost everyone had a Scout or a Range Rover, for the backroads.)

In my travels in the Third World, most seem to drive a Toyota Landcruiser.

The Land Rover (now owned by Ford) has its constituency, particularly in former British colonies and with certain international aid agencies, but they were never particularly mechanically reliable (albeit robust).

Toyota seems the preferred, hard wearing, offroad capable roadster.

In my travels in the Third World, most seem to drive a Toyota Landcruiser.

The Land Rover (now owned by Ford) has its constituency, particularly in former British colonies and with certain international aid agencies, but they were never particularly mechanically reliable (albeit robust).

Toyota seems the preferred, hard wearing, offroad capable roadster.

True, the supply lines would be a bit botched up, but then that is where being rich in natural resources comes in useful. Texas still has a fair chunk of resources to draw upon.

Furthermore if we are down to the point of betting on individual localities due to chaos, then chances are, the political boundries of today, are probably not even relevant as new boundires will likely be drawn and fought for as new State entities arise, whether they be made up of fractional pieces of current states/provinces, or conglomerations of current states/provinces. And that applies to areas outside the US as well. I could easily see Canada, or Mexico doing similar fractionalizing/conglomerations, along with European countries.

In the grand scheme of things it wasn't that long ago that countries like Britain, France, and Germany were just a bunch of warring fuedal territories with each "county" having its own lord. We are already seeing the splintering of African countries into smaller warring tribal based faction due to resource constraints(compounded by bad government), and several South American countres while still maintaining a national "presence" are wrought with internal fighting between factional forces.

If resource depletion continues to march along, how long will it take for more modern countries to come under the same stresses, and culturally will we react the same way, or will we pick a different path?

To date, the two most successful countries in maintaining large national State for extended periods of time including before the presence of FF has been Russia and China, usually through strict autocratic rule and extreme centralization of power.

But then I suppose that kind of touches on the subject of the original essay... In resource constrained situations is Empire/Autocratic rule better(very subjective term I know) than Democracy?

Right up until it gets completely overwhelmed with refugees from Mexico.

Thank God for those Halliburton camps being built!

Those camps are for political prisoners. No refugees allowed.

Water.

Texas is water poor. And the Ogalla Aquifer is depleting very fast.

It's also entirely optimised around a petroleum rich existence-- huge spread out cities, public transport infrastructure is weak to non existent, the prevalent culture is anti conservation (almost a threat to personal liberty to abandon the SUV or the pickup), there is (by design) an extremely weak state government (the legislature is part time and amateur) so collective response is muted.

Conversely the Texas Rangers are effective. So a paramilitary government is not impossible.

And of course Texas is fast running out of oil and gas.

Add to that you have some of the worst inequalities of wealth and income and ethnicity in the US.

So call it a draw. There is much about Texas which is attractive: entrepreneurial spirit, wind and sun, space, dynamic demographics (all those Hispanics). And there is much which it lacks or which could lead it to future chaos.

http://www.fantasticfiction.co.uk/w/howard-waldrop/texasisraeli-war.htm

http://www.fantasticfiction.co.uk/l/fritz-leiber/spectre-is-haunting-tex...

And the world's leader in wind energy, also using some geothermal and solar (lots of both of those). There is also potential to exploit the energy of the ocean via waves and tides.

Cheryl,

I wouldn't count on the island's wave and tidal power being available once TSHTF as the alt-energy infrastrucutre will likely be collatteral damage in the coming Homosexual-Lezbian Pirate war.

I keep forgetting about that. Guess I should just go clean my handguns and rifles again and do a few thou more reloads.

That is unless you decide to join them.

Back in the heydey of high piratery, the 1700 and 1800s, that was how the real pirates of the caribbean did most of their recruiing. They'd seize a ship or outpost, usually staffed by people who were for all intents and purposes slaves, and say to them "hey, you guys are being treated like shit by your overlords. why don't you consider becoming a pirate?"

I'd make a great pirate. Nearly blind in one eye, just need a patch. Already have one artificial joint, the next one will likely be a wooden peg-leg when high tech no longer reaches the island. Cool. Wonder if Johnny Depp (heart) will wander this way. Let's see, twice his age--but maybe I could teach him a thing or two....:-)

Frankly, I'm going to really miss high tech if the collapse is so fast that I don't get my next set of artifical joints here in our isolated outpost. We take so much for granted.

A while back, I told my dad (age 84) that I thought his generation really had the best of everything (excluding the wars). They had the world before pollution got really bad, before population got too overwhelming, and yet got to experience a lot of the wonderful things that the age of oil enabled. And yes, they had hard times too, but they still had the resources to pull out of those hard times. He will also probably die before it gets too horrible. He was always one of those people who thought the economy should trump everything -- especially green stuff. To my surprise, he agreed with me100% and thinks everyone else is pretty much screwed. He agrees we went too far in using/abusing the environment, using its resources, and putting too many people on the planet. It started to really hit him a few years backs when his previously life-filled fishing hole quit offering up fish and his once quiet rural street turned into a noisy highway.

You're twice Depp's age, and so is your dad? What gives?

Well, I'm not really twice Depp's age--I just feel like it sometimes. How old is he anyway since I can't remember? I'll be 58 in 2.5 weeks. I probably have a generation on him, but not 2 gens.

Hey, the older you get the younger everyone else looks.

43 wikipedia has a nice file on him

Hey, so I'm in the ballpark of a "slightly older woman."

Right, dream on you sully wench...

I heard that an 80+/- old friend of my folks thought I was really good looking. Not bad for a 42 yr old at the time...

My grandmother passed recently, was 86. She knew how bad things were getting. I showed her the Fortune article with Richard Rainwater . . . her reply, "looks like it's your problem. I'll be gone by the time that hits and thank God for that."

I agree regarding the "Greatest Generation". Yes, they had challenges and problems but they lived a time where things got better on pretty much all fronts from after WW II until about 1973-1979. Although if you had played your cards right you probably did not notice until recently and even then you may only have noticed by mostly watching the struggles of your Baby Boomer kids and "13ers"/Millenial grandkids.

And then she told you to sell the shop and buy a pirate ship?

Yep she did. "Arrgh matey!"

That's one hell of an exception.

World War I. Circa 20 million dead (on a population of c. 1.5 billion). Over 3 million French men alone ('the Lost Generation'). Then 20-40m dead in the subsequent flu (we don't really know how many).

The Great Depression. The US had 25% unemployment. That's unemployment of men (and probably not black men, at that). Women didn't count. The Dust Bowl blew away, and hundreds of thousands lived in refugee camps ('Hoovervilles') outside the major cities.

The Spanish Civil War. 1 million dead.

World War II. Closer to 80-100m dead. Opinions vary: 25m Russians for sure. Perhaps 5 million Germans. 6 million in the Holocaust. 100,000 died in Tokyo alone in *one night* from firebombs, and something like 70,000 in Dresden. At least 3m Indians starved to death in Bengal in 1943-44, the British were too busy fighting the Japanese to do anything about it. Probably at least 20m Chinese died between the 1936 invasion of China by Japan (really the beginning of WWII) and the end of the Civil War in 1949. Another 25m or so would die in the subsequent purges and then the starvation of The Great Leap Forward.

US dead in those 2 wars were of course far, far, fewer. Maybe a million in total.

If you are American, and male, of course you also had Korea and Vietnam. So your chances of serving in a war, if you were born anytime after 1921, were quite high.

If you were black and American, you had to live through the Civil Rights period and what came before it. If you were gay, what you did was actually illegal, and people went to prison for it.

Let's say our parents' generation was at times foolish with the environment (although the Clean Air Act passed in 1972). They used antibiotics too freely. They sprayed too much DDT (but they stopped). They shouldn't have invented Chloro Fluoro Carbons (CFCs).

There were plenty of warnings (The Limits to Growth in 1970, the Brandt Report etc.). Some were heeded, some were not.

But in the 1980s and 90s the world, and particularly America and the UK, went on a personal greed kick.

I find my parents are much more community spirited and conservation minded than my generation. You don't have to explain to my father about using low energy lightbulbs or not leaving the door open. He's always driven an economical car.

Whereas my peers drive me to distraction with their waste.

Yes, the wars were huge exceptions. My dad served in the military in WWII and still agrees that his generation had it the best. But their values were generally better, the planet was in better shape, etc. I dare say that were we to face the great depression again, I don't believe for a second that people would work together and help each other as much as they did in the 30's. This time it will be eat or be eaten. Our society has gotten very rude and greedy.

Not all of the above applies to ONLY his generation--it applies to several generations. And there's a good chance we will experience nuclear war in our lifetimes. The sheer horror of that pretty much trumps everything.

It is probably not a coincidence that those wars happened at the same time as the good things that you mentioned. Churchill blamed the horrors of World War I, compared to the elitist colonial wars he served in, on "technology and democracy." You also can't fight total war without a public-spirited citizenry willing to make sacrifices... unless you figure out a way to do it with credit cards, which our leaders are currently attempting.

Believe me, better (so far) to have been born in 1960, than in 1900, or 1926. Almost anywhere in the Western World, let alone the Eastern.

Our problems we can do something about. World War I, and II, and the Holocaust, and the Spanish Flu, and the Great Depression, people were just caught in the middle and had to make do.

I wondered sometimes why my parents were so conservative. But when you had uncles dead in World War I, cousins and classmates dead in the second world war, who had marched into Belsen and Auschwitz, when you yourself had served in a grotty jungle war in South East Asia...

when you had seen your parents' business wiped out by Depression, and lived on public handouts of food, when you had seen your mother feed men who came to back porch, asking for a cup of soup, men just like your father, who had lost everything...

We are a blessed generation.

"My granddad was a pirate, my dad built ships, I'm an attorney for a shipbuilding conglomerate, my son will be a pirate."

Attorney, pirate, what's the difference?

One of? Who would that be tstreet? Pimentel?

90% of the scientific community have proven him wrong on corn ethanol and yet you continue to propagate his fallacious assertions... nice work.

The point of the comment was that the skepticism about corn ethanol is not a California centric phenomenon. I wasn't propagating anything regarding the validity or invalidity of Pimental's analysis. Robert Rapier, of course, can speak and has spoken for himself on this site.

But as long as you've brought it up, I personally believe that corn ethanol, at least, has a rather small positive impact on our net fuel liquid resources considering its impact on corn resources. Considering that the American public is bearing direct subsidies for the ethanol and indirect subsidies in higher crop prices, for a rather minimal improvement in fuel resources, the program does not seem like a good one in its present form.

It remains to be seen how useful cellulosic ethanol will be. I think it is premature to conclude that it will fair better than corn ethanol.

You, Snytec, are a malicious fool, a leech to boot. You have no concept of how an economy functions, apparently self-contented in a bovine notion that EROI doesn't matter. This notion indicates you haven't a clue about the function of investment.

Mostly, I just ignore your nonsense, but to ignore your distortion regarding Pimental's place in the scientific community would be a discredit to TOD.

Where is your 90%? How many of those scientists who argue for a methodology that allows a claim of a small energy return for ethanol (North American ethanol), are independent of a political or commercial agenda?

Is it your personal mission in life to keep the ethanol industry latched onto the public teat? Is that why you haunt TOD, posting your endless misrepresentations and disinformation? Take a break. Keithster will fill in for a while.

If you can't debate me empirically without the ad hominem attacks... then don't bother.

I've posted the literature to back up all my assertions -including those that destroy Pimentel's claims- time after time.

I challenge you Toiler to prove me wrong.

Prove me wrong that Pimental's claims re: the EROI of corn ethanol, are anathema to the results found by 90% of the scientific community.

And California gets its food by pumping water from somewhere else (if only intra-state).

It's likely California will give up on agriculture (at least southern California) and in our lifetimes.

The water is too valuable for other activities.

I thought the flyover states were arcane and irrelevant.

And the majority of the USA, and determine who is president and who controls the Congress, and hence the Courts, military, police, etc.

These days Tainter's (and Homer-Dixon's) view of the fall of Rome looks a bit dated.

Take a look at The Fall of the Roman Empire:A New History by Peter Heather (2005)

Main points:

The archeological record does not show widespread agricultural decline. Many areas were going gangbusters and had never been better.

What archeology and the written record do show is that living adjacent to the Empire for centuries caused the barbarians to unite into fewer (and larger) polities. Their own farming output and population surged as they adopted better farming methods and traded extensively with the empire.

According to Heather, Rome did not run out of gas, it was overwelmed. And the forces that overwelmed it were in great measure a product of a dynamic that the Empire itself set in motion.

I suspect that wood--a critical energy resource--depletion played a major role in the decline of Rome, and other civilizations as well. See John Perlin's book, "A Forest Journey," where he explores the role of wood in civilization in-depth. If you chose to read this text, you'll discover very disturbing parallels between wood scarcity in the past and the idea of oil scarcity today. This text is an eye-opener.

-best,

Wolf

Yes. I also suggest reading Alexis Ziegler to more fully grok what he calls the long curve of resource availability driving the short curve of political

(d)evolution:

The societies that have evolved into democracies include the Greeks, Romans, numerous European nations, and U.S. Americans. In each of these societies, a central powerful state with a land-owning elite grew first. (The land-owning elite was not as entrenched in America.) As these cultures grew, they sent their militaries into foreign lands, and became colonial powers. As the wealth of colonial exploits arrived back in the motherland, a mercantile class grew up to trade these foreign goods. Over time, the volume of goods arriving from the colonies grew, and the power of the mercantilists grew, until finally, they were able to challenge the power of the landed elite. Thus civil liberties were expanded to the mercantile class. (It is hard to conduct business if you constantly have someone plundering your profits, or looking over your political shoulder.)

So what's this got to do with us? The thing that is important to understand is that the expansion of civil liberties has, in our culture as in every other, followed the expansion of resource extraction. When a society has an enormous inflow of resources, from colonial exploits or from fossil driven extraction, it is economically useful to have a large group of people who are personally empowered. Those empowered souls serve as entrepreneurs, mercantilists, and consumers, driving the economy forward. Democracy can be defined as the ability of groups of people to use their economic position to assert political power. In the absence of an expanding economy, democracy does not expand. In the U.S. after World War II, the income of African Americans was expanding rapidly, as it was for women. This is not coincidental with the success of the movements to gain civil liberty for these groups. But we must also heed the lessons of the Greeks and the Romans, because as their resource base declined, they reverted to military dictatorship. We would be unwise to imagine that their will to freedom was any less than our own.

http://conev.org/primer.html

also see these at http://www.conev.org/:

Listen to an interview of Alexis about his book Culture Change on WNRN radio from January 28, 2007. (It's a one hour interview, in MP3 format.)

Concious Cultural Evolution, Understanding Our Past, Choosing Our Future, A book by Alexis Zeigler

Concious Cultural Evolution, A Primer

Where Do We Go From Here?

Drug Wars, The Burning Times

The Past and Future of Women's Rights in America

Why Are We So Stupid?

Biodiesel and Other Fuels in Ecological Perspective

Biofuel and Genocide

Peak Oil, Biofuel and Culture Change

This mirrors a thesis of mine that freedom is not a value written in the foundation of the universe, it is an adaptation of people to particular environmental and historical circumstances and if circumstances change, freedom will be jettisoned for a new value system that better adapts to the new environment.

Yes! I just wrote a long reply down-thread about this. The Romans burned through hundreds of years of old-growth forest. It wasn't a lack of food that did them in, it was progressively more expensive transport and declining production of their primary form of energy - wood. Their fossil fuel was the centuries of stored sunlight found in trees.

I have argued (in relation to Spain rather than Rome) that empires feed those they have close connections with, sometimes to the extent that they become effective competition for resource concentration. Those regions which benefit from the export of capital from a political centre are therefore arguably in a third category of their own.

If they are able to reach a certain 'critical mass', then they may survive the loss of exported capital from a fallen empire and go on to become centres in their own right. Arguably one could follow a rough progression of economic and thereafter political power, for instance (beginning at an arbitrary point) from Arabia to Spain to the Netherlands and Britain to America and perhaps on to China, with each new centre capitalizing (pun intended) on its connection with a previous centre of power.

Of course the same process going on concurrently with regard to other geographical centres, their surrounding areas and their distant peripheries complicates the picture.

Some geographers have argued that this northwestward shift of power centers over time, from Mesopotamia through Greece/Byzantium to Rome and on the NW Europe, follows an overall warming trend, making possible an expansion of agriculture and population.

Obviously a much richer discussion of this point downthread...

So, is rome/germanic an example for us/china?

The latter two must compete now in becoming more energy efficient, and fast.

There is also the aspect that the various peripheral social groupings learned how to deal with Rome on Roman terms - that is, their military abilities grew, while Rome's remained static. In areas along the Rhine, this meant that the people living there learned well enough to follow the Roman military roads back to Rome - often as mercenaries, and then as people with the drive to go into business for themselves, instead of being employees (a bit of twisted humor there, if you know anything about real estate guru speak).

And notice how these discussions tend to focus on Rome, and not such minor parts of the 'Roman' Empire as Alexandria or Constantinople, as they don't fit anywhere near as well in the narrative of a declining Rome requiring ever more conquests to maintain a highly structured society - after all, Constantinople was essentially newly founded while the city of Rome began its decline.

And nobody much talks about the Persians throughout this entire period - their culture and achievements were notable, but are generally ignored.

Rome is a metaphor for many things, and within Western societies, this has a major effect. Facts are less important than perceptions, which itself is a perfect metaphor for our current framework.

Yes, glad to see that someone has picked up on this. Rome is a remarkably central metaphor for 'Western' civilization - so much so that complete and utter BS that would be laughed at by everybody in any other case passes for conventional wisdom as far as Rome is concerned. And this after 1500-odd years... I shudder to think what ridiculous misconceptions our distant descendants (not that there are going to be any, but still) will hold about us.

Rome didn't collapse because of an energy shortage. It's simple: Roman society was solar-powered, and so were the societies that came after it. So, where is the energy shortage? It is not changes in actual productivity that caused the fall of Rome, but the social facts associated with productivity. Put more plainly, people were evnetually taxed beyond endurance (so much so that even many formerly wealthy people couldn't take it), and soon no one could be bothered to defend the Empire as a political entity any longer. The rich retired to their country villas and stayed put for good. The poor welcomed the 'barbarians' as being a possible improvement on their former overlords. The end.

Enough of these overdrawn analogies between Rome and the modern world. Rome ran a brutal empire, so does the current suzerain. There the analogy ends. It is probably more productive to watch endless repeats of 'Gladiator' than engage in this sort of overdrawn theorizing.

I agree with you Franz. The thermodynamic explanation IMO erroneously tries to shoehorn a complex historical mega-event into a simple theory. I have lately been reading Peter Corning's book 'Holistic Darwinism.' Contrary to the sound of the title, it is a very densely scientific read (40 pages of references). He discusses the common mistake of conflating the concepts of 'entropy' and 'order' and explains how they really are not the same, a mistake that is made in this post and the basis of what you are saying, i.e. there are many more factors involved in what constitutes 'order' than simply the distribution of energy.

The flaw in this article is that it says that the collapse was a food induced collapse. This was not the case at all for Rome. The collapse was the result of a decline in the effectiveness of the Roman military's ability to extract tribute from an increasingly large empire due to simple logistical issues and the increasing military sophistication and revulsion of barbarian tribes.

I would say that Tainter holds up well because he effectively contrasts the method of Diocletian and other later Roman rulers for dealing with the fall of the Western Roman empire with the methods that the Eastern Roman Empire(Byzantines) used. The former tried to tighten the screws by raising taxes and hereditarily binding farmers and other professions to their duties. The latter completely reorganized their society into a far simpler and more efficient structure and survived for 1000 years.

I'm not arguing with Tainter here - I agree with him. I didn't say it was a food collapse, but rather a catabolic collapse where the empire consumed its own capital (farmland, peasantry, wood etc) and lost the ability to concentrate wealth (and therefore energy) from its periphery.

Stoneleigh,

You really should read Heather's book (referenced upthread).

On a number of points, things are more complicated than one might think.

For instance, the city of Rome ceased to be the administrative centre of the Empire centuries before it's fall. The emperors no longer lived there and rarely bothered to visit. Other centers closer to the frontier, like Trier, grew substantially in wealth, status and culture.

The idea of Rome as a huge spider sucking juices from an ever increasingly impoverished hinterland doesn't hold up according to Heather's account of recent archeology.

All of these arguments about what REALLY happened to cause Rome's collapse remind me a lot of the arguments about Hubbert's analysis and how to actually perform the analysis and what it really means....oh the parallels...

Precisely! I was about to make that point myself.

It's not a bad exercise: attempting to take the square root of the Roman empire. But there are severe limits.

Tainter, Homer-Dixon and Hubbert are all alike in that although they do provide some very nice insights , they supply very little predictive power.

The real world is just too messy.

The fall of Rome has many similarities with Saudi Arabia's 2006 8% oil production decline. There is a new theory about it almost every day.

"...but rather a...collapse where the empire consumed its own capital (farmland, peasantry, wood etc) and lost the ability to concentrate wealth (and therefore energy) from its periphery."

Just like we just did. Done sold the farm. Dug us a debt hole so deep, default is the only way out. Shipped all the jobs overseas. About to turn all the food into ethanol. Abolished bankruptcy. About to reinstitute indentured servitude. Slavery by any other name. When we start losing loved ones to starvation I hope we have enough strength to finally stand up for ourselves.

I recently read Heather's "Fall of the Roman Empire," and I have very mixed thoughts. Yes, he brings in a lot of interesting counter arguments from recent archaelogy, etc., and paints a very different picture from that which we have been used to.

On the other hand, it is clear that he has a very definite agenda, and that this book is part of an ongoing quarrel with other historians. I'm not convinced he is being intellectually honest.

After reading his (perhaps selective) documentation of how allegedly robust Rome was, it seems inexplicable that Rome collapsed as it did. As soon as the barbarians penetrated the Rhine frontier, they no longer encountered any significant Roman resistance, either from the center or the rural elites.

Heather shows how the rural elites cut a quick deal with the newcomers, who demanded far less taxes, thus depriving the center of revenues, food and resources. But one definitely gets the overpowering sense that Italy itself was stripped down, bankrupt, and incapable of raising forces to defend itself. The center fell with very little resistence, after which little remained except the culture.

One additional observation: Heather says the population of the city of Rome was 1 million under Ceasar Augustus (just before Christ); while Prof. Daileader of William & Mary documents 400,000 in the 4th century, and 15,000 in the 8th century. Thus, Rome as a city peaked when the empire peaked, and had declined considerably by the era of barbarian invasions.

(by the way, hi folks, after a month and a half my server is working again...)

The quick deal, though (in Heather's view), was not struck because the empire was in shambles in comparison with its former self but because Rome's forces were already inconveniently tied up fighting the Persians in the east.

Tax concessions to barbarian 'immigrants' didn't cause the revenue shortfall. Taxes dried up because the Goths trashed the place and severely damaged the tax base.

This wikipedia article accurately characterizes his position:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fall_of_Rome

A quotation:

Thanks for the good link to the wiki review.

" [Heather} also rejects the political infighting of the Empire as a reason, considering it was a systemic recurring factor throughout the Empire's history which, while it might have contributed to an inability to respond to the circumstances of the 5th century, it consequently cannot be blamed for them. Instead he places its origin squarely on outside military factors, starting with the Great Sassanids."

This relates to perhaps my greatest critisism of Heather's book.

It is precisely the organizational weaknesses which make Rome dysfunctional. They could "afford" to have regularly recurring, highly destructive civil wars when there were no enemies. But in the presence of the Gothic incursion into Gaul, the emperor put off confronting them until he defeated all his internal Roman rivals. By the time that was completed, the outclassed legions failed to make headway against the superior arms and tactics of the barbarians.

Also, Heather's portrayal of the defection of the rural elites seems to clash with his conclusions. The huge burden of Roman taxation, and the light taxation levied by the barbarians, directly goes to Tainter's argument that the costs of maintaining Roman institutions had far outstripped any benefits. And in the face of barbarian invasion of Italy itself, there seems little evidence of any attempt to raise a militia. The citizenry of the heartland seems not to have cared who ruled them.

Yes, the barbarians did trash Italy, but reading between the lines of Heather's book, it seems there wasn't much left there in the first place; a few rich landlords (who were willing to cut a deal with invaders) lording it over vast expanses of slaves who had nothing to defend.

I would like to recommend Dale and Carter's "Topsoil & Civiliation", an out of print classic that is available for downloading. It has been clear for some time that Roman agricultural practices severely depleted soil fertility, and thus Italy was probably already in population decline by the fifth century. Once the Vandals took Tunisia, Rome literally had no food to eat.

I must admit i am somewhat under-whelmed about this energy analysis of roman decline not least the idea social complexity dissolved as described.

agriculture decline was a factor of thoughts in some regions but not others, moreover the centralization of the Roman empire was not as focused as the writer makes out. many regional cities had there own hinterland.

Rome collapsing was the function of many things including a transition into something else..essentially the eastern empire never imploded as the western empire did. Political corruption was a large part of it, that and population pressure displacing people into the empire

you could argue overshoot of some kind but the analogy to our present situation is stretched

statements that the crisis of the third century and diocletian reforms de-powered the hinterland of the empire to pre invasion levels strikes me as a UK based archaeologist as largely fiction. It is possible that trade across the roman world contracted to more local distances but this really was a good thing in some ways... the increasing use of local wares rather than Samian pottery made In central gaul can be looked at a increased complexity at alocal level or a breakdown in the cohesion of the roman empire (was it a good thing anyway?)

the abandonment of Roman cities in the UK occurs in the main in the fifth century and is preceded by 2 centuries of fortification dating back to the crisis of the third century.

local conditions can have a major bearing on abandonment and economic success in the roman era.

However some arc of truth may exist in the argument concerning entropy in a more general sense in that the concentration at a local level was interrupted by growing anarchy and warfare and thus its effect on commerce.

I believe there is some evidence for agricultural decline on environmental grounds in Roman North africa but I'm no expert on such matters. I saw some stuff concerning deforestation but would be interested to know how such calculations were done?

I think my main point is its too easy and perhaps unhelpful to make these direct comparisons

Boris

London

Asebius,

Yes, I am familiar with that line of thinking, and it's another one that seems to have repeated through history....and explains a great mystery...

The Greeks likewise had created offshots that eventually learned all their tricks, built organizationally/culturally away from the center, and then came under assault by those using a dynamic that the Greeks themselves had set in motion to take over from where Greece left off. One of these was of course Persia....and another? Rome itself.

The Vikings and Nordic cultures likewise set in motion forces which would create the replacement empire from the edge of it's old influence sphere....The British Empire and the Francs.

It seems that the real issue here is cultural and has very little to do with energy per se. Now to the great evidence of this, and the great mystery:

There is a people that by virtue of geography, were blessed for a longer time span with access to more calories, kilo-joules, kilowatts.....I don't care what measurement you use....but each person had access to more raw energy than any people on the face of the Earth per capita, in biosphere to conquer and harvest, in land space to farm, in sunlight and mild warm weather....even from the sea by virtue of a HUGE coastline....all of this shared by a tiny relatively peaceful people, for thousands upon thousands upon thousands of years.

And what was the result? NOTHING. ABSOLUTELY NOTHING!!!

I am of course referring to the mystery of the Australian aboriginals. The religion and stories of these people prove that they had great minds. These were not and are not stupid people. They are inventive, they are resourceful, and yet, they never moved beyond the stage they reached probably 50,000 years ago. Why? It certainly wasn't lack of energy, this new catch all explanation for all of history. (How silly....there are too many examples that repudiate this simplistic "energy based" view of history to go into here), but the Australian aboriginals seemed to suffer from that most culturally deadly of all ailments: Lack of cultural cross pollination and competition. It is this that creates goals, comparisons, competition and new synthesis. Energy is ALWAYS there. Without cultural drive and goals, energy is garbage.

I have tried to tell you all.....it's the GOAL, the AESTHETIC that matters.

The energy is here, we are awash in the slop. (NOTICE, I said "energy", not oil.

Oil is just one form of energy, and when you really look at it, not that great of one either)

"According to Heather, Rome did not run out of gas, it was overwelmed. And the forces that overwelmed it were in great measure a product of a dynamic that the Empire itself set in motion."

Or as the Ancient Egyptians said in their declining days of the Helenistic tourists trysting around on the pyrimids...."to think, we taught these upstarts all they know...."

It's called history. It's still going on. There will be wealthy, high tech cultures a dozen years from now, and one hundred years from now, probably one thousand years from now. They will find the energy. Because they will have the goals, the drive, to do what we say cannot be done. The only question remaining is will we, or some variation of us culturally be among them. or will we, like Carthage (gee, did they run out of energy....?), be put out of our whining and complaining by some outsiders who still believe that there are things that can be accomplished? Our offspring will judge us by the path we take now.

Roger Conner Jr.

Remember, we are only one cubic mile from freedom

Indeed. And, oh do we so much want to substitute a formula or a graph for messy history (and culture!).

I just realized that in presenting Heather's views, I neglected to mention the Huns. Mysterious to this day, they are that powerful random element that makes calculation impossible and that make history history to us poor mortals.

Two pieces of the picture are missing from the above review.

First, becoming embedded in a larger system can create efficiencies in energy production that benefit both the hinterlands and the center. One or two Roman legions can provide peace, security, and stability that allows production to flourish and misfortunes like war and disorder to be minimized.

Second, the great expansion of the Roman Republic and later Empire was coincident with a period of warming in Europe so that the productivity of agriculture increased on its own. The Romans just came along to organize it and take advantage of it. For example, wine grapes were grown as far north as the Midlands in England, a place with no present production.

I detect a bit of Marxist "zero sum" thinking in the above article. Just as a farmer can make the net yield of a plot of land increase through his energy inputs, so too can capitalism. For America to play global policeman means that other nations can reduce their overhead for armaments and standing armies. Look at Europe's defense spending while living under American protection under NATO - it's a fraction of their GDP compared to the US.

The decline of the Roman Empire was also coincident with a return of cooler temperatures, shorter growing seasons, and lower agricultural productivity. They system collapsed because the net solar energy available couldn't support it against the pressures of grassland marauders from the north.

A more balanced and broader discussion of ecosystems, energy, and civilizations can be found in Howard Odom's books.

That said, I'll probably pickup this one and read it.

This article is not a review of Homer-Dixon's book, although a link to a review of the book can be found near the beginning. It is an attempt to explore the further implications of applying thermodynamics to empire.

I'm not a Marxist, but only entropy is really a positive sum game.

Well we all know that our sun will engulf us in a supernova, but this is a couple of million years off. So entropy is really not that relevant for the next billion years.

With globalization the next collapse of social order will be global, just because we became so intertwined. No resilence here.

This doesn't change the point you're making, but...

Our sun doesn't have enough mass to support a supernova. It about five billion years time, the Sun may have expanded enough in the "red-giant" phase to have occupied the orbits of Mercury and Venus, perhaps the Earth. Due to friction with the expanding outer gas envelope, these worlds would likely fall into the sun during the slow expansion phase. Maybe Mars, too. The sun will eventually go "nova", which is a milder stellar eruption than a supernova.

Perhaps the most important stage in our sun's evolution, for life on Earth, will be sooner than five billion years. Main-sequence stars like the sun become brighter with age. Roughly speaking, the sun's luminosity increases by about 1% every 100 million years or so--ah, perhaps a little less than this. When the sun was young, it was only about 70% as bright as today. With this slowly increasing output, it is anticipated that the Earth will experience a runaway "moist greenhouse" in about 0.5 to 1.0 billion years. With the oceans boiled away, this Earth may become somewhat of a twin to Venus... Sizzlin’!

-best,

Wolf

A pity we've squandered our one-time shot of oil wealth.

With a bit of foresight we could have used a captive asteroid to transfer orbital momentum from the larger planets to the earth, and had its orbit gradually widen, thus buying it another billion years or two... perhaps.

"For example, wine grapes were grown as far north as the Midlands in England, a place with no present production."

Um, there's at least one vineyard in Scotland, and there's plenty in England.

See here.

The English have, improbably enough, been winning awards with their wines lately, so I don't know why this whole "no English vineyards" stuff persists.